Generating math hints with large language models

When a student gets a math problem wrong, teachers sometimes provide hints to get them on the right track. The core idea behind giving hints is to return the student to a place of “good friction” with the material by reducing their cognitive load enough for them not to be overwhelmed but not so much that no learning occurs.

When students are trying to solve a problem in a digital interface, presenting an automated hint is appealing: the student doesn’t need to wait for the teacher to move forward with a problem, and the teacher can focus on students who are more stuck. For automated hints to be helpful, they have to contain some information about the problem. As Jean McKendree argued back in 1990, “receiving some information about the nature of the error is more useful than simply knowing that an error has been made” (McKendree, “Effective Feedback Content for Tutoring Complex Skills”, 1990).

However, designing automated hints is challenging. The effectiveness of hints is highly contextual (Inventado et al., “Contextual factors affecting hint utility”, 2018), so we might need to create different “types” of hints that are useful for the specific topic, student, or problem.

Creating hints is a time-consuming human activity, partially because students can be stuck on a problem in diverse ways. For this reason, it would be nice to use large language models (LLMs) to generate hints “on the fly” that incorporate a student’s prior work on this problem or topic.

If we want to use LLMs to generate hints, we should understand what makes an effective hint. The research on intelligent tutoring systems (ITSs) describes various hint-giving strategies. The most common approach is a “hint sequence”: multiple hints that progressively reveal more information about a problem (VanLehn, “The Behavior of Tutoring Systems”, 2006).

A specific hint sequence is Point, Teach, and Bottom-out:

- Point: tell the student where to look, without giving the answer away

- Teach: give the student high-level instruction about how to solve the problem, without giving the answer away

- Bottom-out: provide the student with the precise computation they need to solve the problem

There are many basic variants of this approach. For example, here’s a slightly more specific framework (Stamper et al., “Enhancing the Automatic Generation of Hints with Expert Seeding”, 2010):

- Re-state the goal: what is the student trying to do in this problem?

- Indicate the problem-solving approach: how the student should solve the problem.

- Set up the problem: put the numbers in the problem into the problem-solving approach i.e. ‘finish setting up the problem’.

- A bottom-out hint: tell the student explicitly what to do.

Inventado et al. present a nice summary of design patterns in giving automated hints (Inventado et al., “Feedback Design Patterns for Math Online Learning Systems”, 2017).

Can LLMs generate useful hints?

I am not aware of research exploring the utility of LLM-generated hints. So, I did some preliminary work exploring hint generation for Rori, an online chat-based math tutor. I won’t talk in detail about the technical approach I used; one technique I explored to improve the quality and relevance of hints to a student’s work is retrieval augmented generation, which I also applied to improve answers to students’ conceptual math questions. Read that post for more details.

I created the llm-math-education Python package to implement hint generation with OpenAI’s GPT-3.5 LLM.

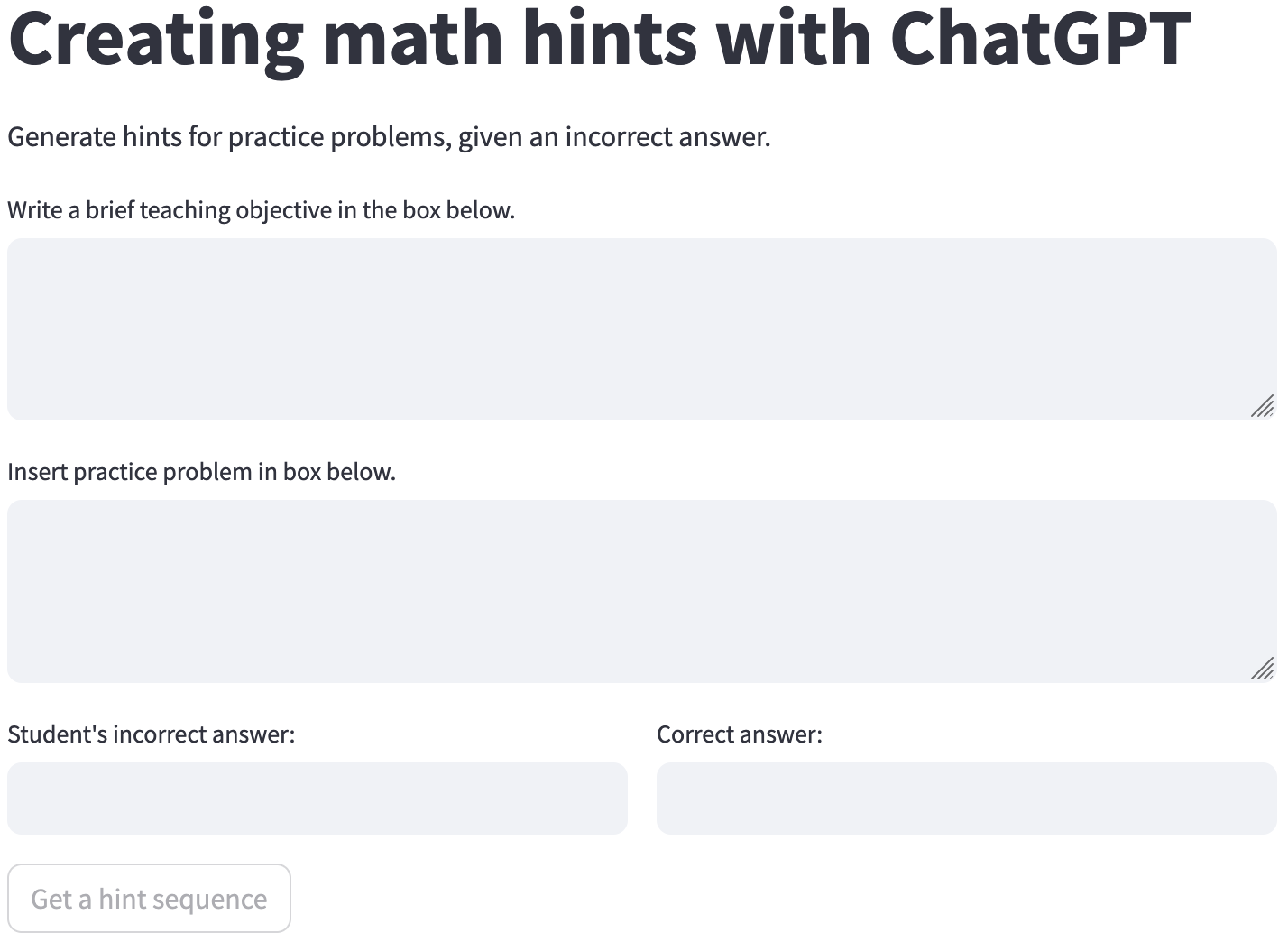

In collaboration with The Learning Agency and Rising Academies, we released the Math Hint Generation Chatbot (press release) to demonstrate the potential utility of hint generation.

You can try the demo, hosted on Streamlit.

You can try the demo, hosted on Streamlit.

The basic idea of the tool is to make it quick for teachers to write hints for math problems. For example, Rori has a variety of nicely-written hints (in the “hint sequence” style) delivered after multiple incorrect attempts at a problem. While those hints help the student with the problem, they don’t take into account the student’s incorrect answer that triggered the hint in the first place. The reason for that omission is simple: Rori has hundreds or thousands of multiple-choice questions that a student might see, each with multiple incorrect answers that could hypothetically have a pre-written custom hint. Add to that the free-response questions where a student might produce dozens of plausible yet incorrect answers, and that’s more hints than any teacher could write!

The tool helps teachers write hints in two ways: (1) by focusing their attention on vetting or editing an LLM-generated hint that follows “hint sequence” best practices rather than writing a hint from scratch, and (2) by enabling teachers to evaluate the quality of hints that would be generated by the LLM if the system was used “on the fly”. That second point is important; teachers shouldn’t blindly trust that an LLM will produce reasonable output for a specific problem, so exploring the performance of the system on a few plausible incorrect answers will allow the teacher to build confidence in the hints’ quality… or to choose to write their own hints.

Evaluating the quality of a hint is harder than it looks. For many teachers, it’s more of an “I know it when I see it” situation, and as mentioned previously there aren’t widely-adopted best practices or design patterns for creating effective hints. I wrote an opinionated LLM prompt based on the research on hints that I’ve been exposed to, but educators are likely to have different and more informed perspectives on what makes hints effective. For the designers of ITSs, those perspectives are critical. I’m excited to release this tool partially as a provocation that encourages educators to share their knowledge so that designers can improve the feedback given to students - hopefully making everyone’s life easier.

To use the Math Hint Generation Chatbot in a real setting, we would need to adapt it to the particular context in which a teacher is working.

- For lesson planning, it might provide a starting point for a teacher’s notes on how to give hints during a problem-solving session. In that context, we would want to integrate with a teacher’s lesson-planning process and take into account the lesson context and when the teacher might be deploying these hints (e.g. as notes to provide to a circulating TA, in small groups during a think-pair-share, etc.)

- For tutors, it might be useful for on-the-fly idea generation. The tutor might know that an approach is mistaken, but find it difficult to articulate why or how to move forward on the problem without “giving away” the answer. In that context, we would want to design an interface that can be used quickly without distracting the tutor. (As a former middle-school math tutor, I would have loved a tool like this! But only if it didn’t disrupt my interactions with students.)

- For online education, it might be useful for helping educators write the hints that will be used by students when they make misteps during problem-solving. In that context, hints will need to align with the broader context of the ITS, making use of whatever information is available to improve the relevance of hints.

A final thought: one of the reasons that hint generation is an appealing research problem is that hints represent information that can be given proactively in response to an error rather than reactively in response to a student’s question. For the engaged student, LLM-generated information might be useful for accelerating their learning. But many students are not highly engaged or may not have the confidence or knowledge to request a useful hint - particularly when using a rigid ITS. For these students, hints offer the seductive promise of intervening in a student’s learning to provide information that will keep them thinking about the problem and prevent a frustration spiral. Of course, we need a lot more research on when and how to give hints: there are real risks to proactively providing hints during problem-solving. But, with the right design approach, I’m confident that we can improve hint generation systems in order to benefit the least-engaged students.

In the shorter term, I think it makes more sense to focus on helping teachers write lesson plans and worksheets. In putting together the Math Hint Generation Chatbot, I noticed that the hints are not yet consistently reliable enough to show directly to students, but after reading a generated hint I often found myself with a new idea about how I would engage a student about a problem. I hope the demo gets educators thinking about how or if these types of hints might be useful as first drafts that prompt new ideas and higher-quality interactions with students.

For more demos using LLMs to improve education technology, check out “Five New Tools From The AI LEVI Lab”.

Further Reading

If you’re interested in giving hints to students, the following alphabetical reference list may be useful to you.

- Christa Cody, Mehak Maniktala, Nicholas Lytle, Min Chi, and Tiffany Barnes. 2022. The Impact of Looking Further Ahead: A Comparison of Two Data-driven Unsolicited Hint Types on Performance in an Intelligent Data-driven Logic Tutor. Int J Artif Intell Educ 32, 2 (June 2022), 263–296. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-021-00237-3

- Elena L. Glassman, Aaron Lin, Carrie J. Cai, and Robert C. Miller. 2016. Learnersourcing Personalized Hints. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (CSCW ’16), Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1626–1636. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/2818048.2820011

- Gregory Hume, Joel Michael, Allen Rovick, and Martha Evens. 1996. Hinting as a Tactic in One-on-One Tutoring. The Journal of the Learning Sciences 5, 1 (1996), 23–47. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0501_2

- Benny G. Johnson, Fred Phillips, and Linda G. Chase. 2009. An intelligent tutoring system for the accounting cycle: Enhancing textbook homework with artificial intelligence. Journal of Accounting Education 27, 1 (March 2009), 30–39. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2009.05.001

- Ekaterina Kochmar, Dung Do Vu, Robert Belfer, Varun Gupta, Iulian Vlad Serban, and Joelle Pineau. 2022. Automated Data-Driven Generation of Personalized Pedagogical Interventions in Intelligent Tutoring Systems. Int J Artif Intell Educ 32, 2 (June 2022), 323–349. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-021-00267-x

- Mehak Maniktala, Christa Cody, Tiffany Barnes, and Min Chi. 2020. Avoiding Help Avoidance: Using Interface Design Changes to Promote Unsolicited Hint Usage in an Intelligent Tutor. Int J Artif Intell Educ 30, 4 (November 2020), 637–667. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-020-00213-3

- Kazuhisa Miwa, Hitoshi Terai, Nana Kanzaki, and Ryuichi Nakaike. 2013. Stoic Behavior in Hint Seeking when Learning using an Intelligent Tutoring System. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society. Retrieved from https://cogsci.mindmodeling.org/2013/papers/0548/index.html

- Leena Razzaq and Neil T. Heffernan. 2010. Hints: Is It Better to Give or Wait to Be Asked? In Intelligent Tutoring Systems (Lecture Notes in Computer Science), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 349–358. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-13388-6_39

- Kelly Rivers. 2017. Automated Data-Driven Hint Generation for Learning Programming. PhD thesis. Carnegie Mellon University. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/6714911.v1

- P. Sedlmeier. 2001. Intelligent Tutoring Systems. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes (eds.). Pergamon, Oxford, 7674–7678. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/01618-1

- David Wood, Heather Wood, and David Middleton. 1978. An Experimental Evaluation of Four Face-to-Face Teaching Strategies. International Journal of Behavioral Development 1, 2 (April 1978), 131–147. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/016502547800100203

- Meng Xia, Xinyi Zhao, Dong Sun, Yun Huang, Jonathan Sewall, and Vincent Aleven. 2023. Involving Teachers in the Data-Driven Improvement of Intelligent Tutors: A Prototyping Study. In Artificial Intelligence in Education (Lecture Notes in Computer Science), Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 340–352. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-36272-9_28

- Kexin Bella Yang, Tomohiro Nagashima, Junhui Yao, Joseph Jay Williams, Kenneth Holstein, and Vincent Aleven. 2021. Can Crowds Customize Instructional Materials with Minimal Expert Guidance? Exploring Teacher-guided Crowdsourcing for Improving Hints in an AI-based Tutor. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 5, CSCW1 (April 2021), 119:1-119:24. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/3449193