Using retrieval-augmented generation to improve math question-answering

This blog post is adapted from a talk I gave at the NCME AI in Measurement and Education (AIME) speaker series that summarizes a research paper I presented at the NeurIPS’23 Workshop on Generative AI for Education (GAIED).

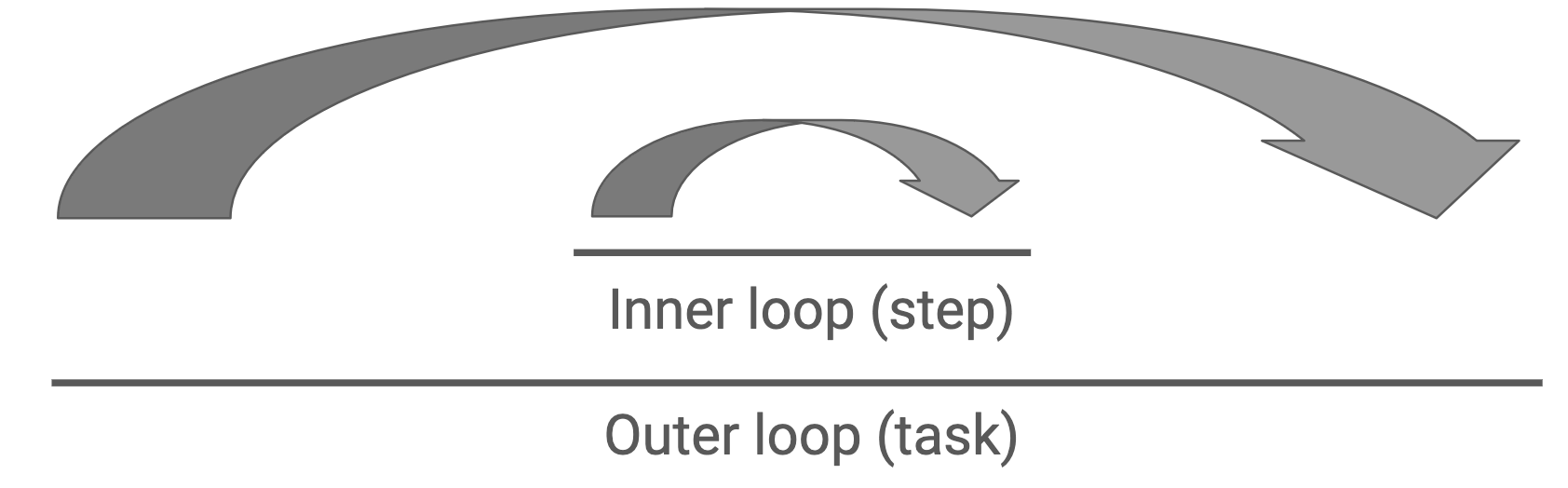

It’s an exciting time for text generation in education. While there are applications in automated assessment, student feedback, and many other areas, I want to focus on 1-on-1 tutoring, particularly as it’s implemented in intelligent tutoring systems (ITSs). Influenced by the writings of Kurt VanLehn, I conceptualize ITSs as having two “loops”: an outer loop where a student selects a task and an inner loop where the student takes steps toward completing that task.

If we want to improve intelligent tutoring systems using large language models (LLMs), most design opportunities I’ve seen target the inner loop. For example, using LLMs to generate hints or hint sequences in response to students’ work. Question and answer sessions can fit this mold too. Q&A with human tutors is one of the most impactful learning interventions we know about, and I like to distinguish between two approaches to math Q&A:

- Procedural Q&A: our goal is enhancing students’ procedural fluency using strategies like step-by-step problem solving for specific math topics. This is an “inner loop” intervention!

- Conceptual Q&A: our goal is deepening students’ conceptual understanding using strategies like clarifying math concepts with concrete or worked examples, providing immediate feedback on a student’s conceptual thinking, and connecting math ideas to real-world problems. This is an “outer loop” intervention!

I distinguish between procedural and conceptual Q&A in part because we know LLMs can be helpful for procedural Q&A (although they make lots of errors). With conceptual Q&A, we’re in uncharted waters. When I’ve seen previous work on conceptual Q&A, it’s framed as an information retrieval problem with a traditional search interface. “I’ll add a search bar to my intelligent tutoring system so that I can search through the textbook more easily.” That is useful, but LLMs are an appealing alternative: we can get (hopefully) factual information but adapted to the language and framing the student uses.

Prototyping LLMs for conceptual Q&A in Rori

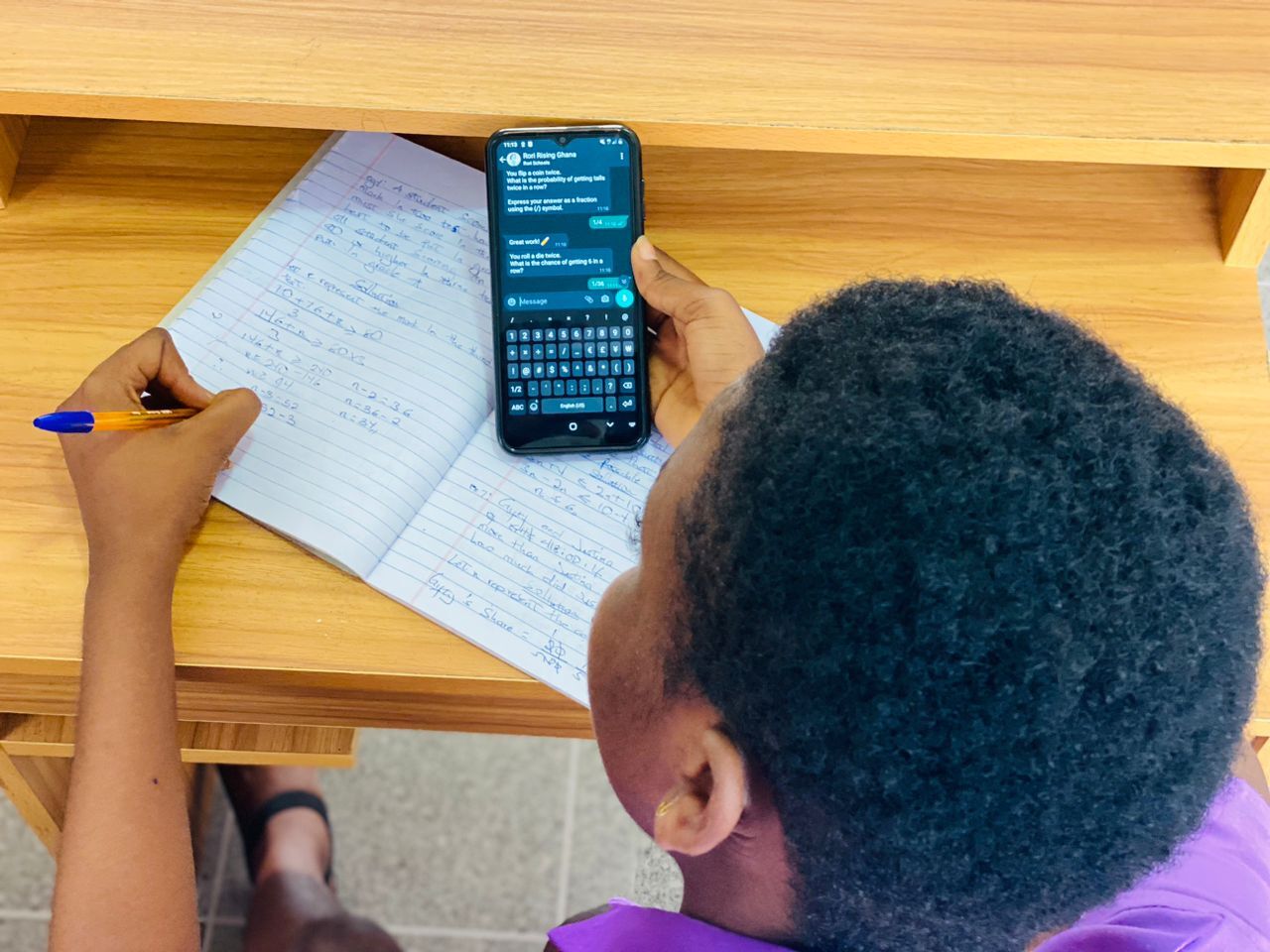

Our research team was particularly interested in conceptual Q&A because we were collaborating with the developers of an intelligent tutoring system called Rori. Rori is focused on procedural support, but at the time didn’t have any built-in conceptual support for students. Rori is a smartphone-based chatbot math tutor used by students both in the classroom and at home. Rori is a product being developed by Rising Academies, an Africa-based education company, school network, and a team in the Learning Engineering Virtual Institute (LEVI). (I conducted this research at the Digital Harbor Foundation, an education non-profit supporting the LEVI program.)

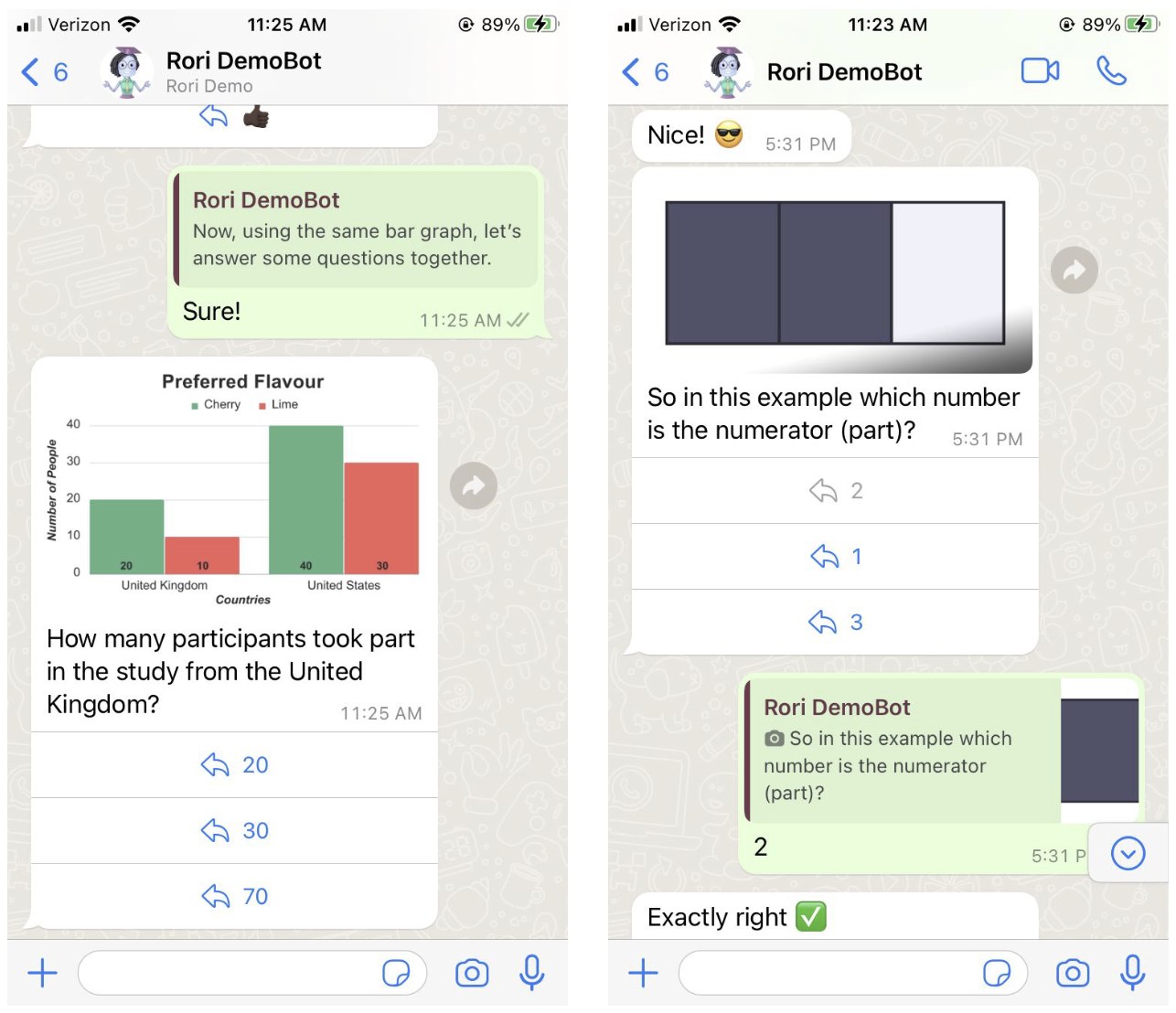

We were excited to improve Rori by prototyping a new feature that uses large language models to provide conceptual Q&A to students. It will help to understand a few details about how Rori functions. Rori is accessed using WhatsApp, and its primary use is delivering “micro-lessons” to students: short lessons intended to introduce students to a single math concept. Because Rori micro-lessons are delivered via WhatsApp, its interface is necessarily inflexible: images and text, with mostly multiple-choice and simple free-response questions.

Our goal was to move beyond micro-lessons to more conceptual discussions that aren’t associated with a single math problem the student is working on. To prototype a conceptual Q&A feature, we need to understand student’s conceptual Q&A needs. Students weren’t asking Rori conceptual questions, so we looked for appropriate data elsewhere. With folks from the University of Florida, who are also involved in the LEVI program, we instead turned to the Math Nation (formerly Algebra Nation) forums to see what kinds of questions students ask.

In the Math Nation forums, we can see what kids actually say to each other; their questions are answered by peer tutors and teachers. I personally went through about 500 Math Nation threads, and I can tell you that the two main things posted by students are (1) memes that range from baffling to actively offensive and (2) homework help. I would call the homework help requests more procedural then conceptual, e.g. “Did I do it right”, “how do I solve this specific problem”, etc.

But there are some conceptual questions as well!

- what is monomial

- How do I add line segments again

- How do I multiply fractions

- How do you know if a number is a constant

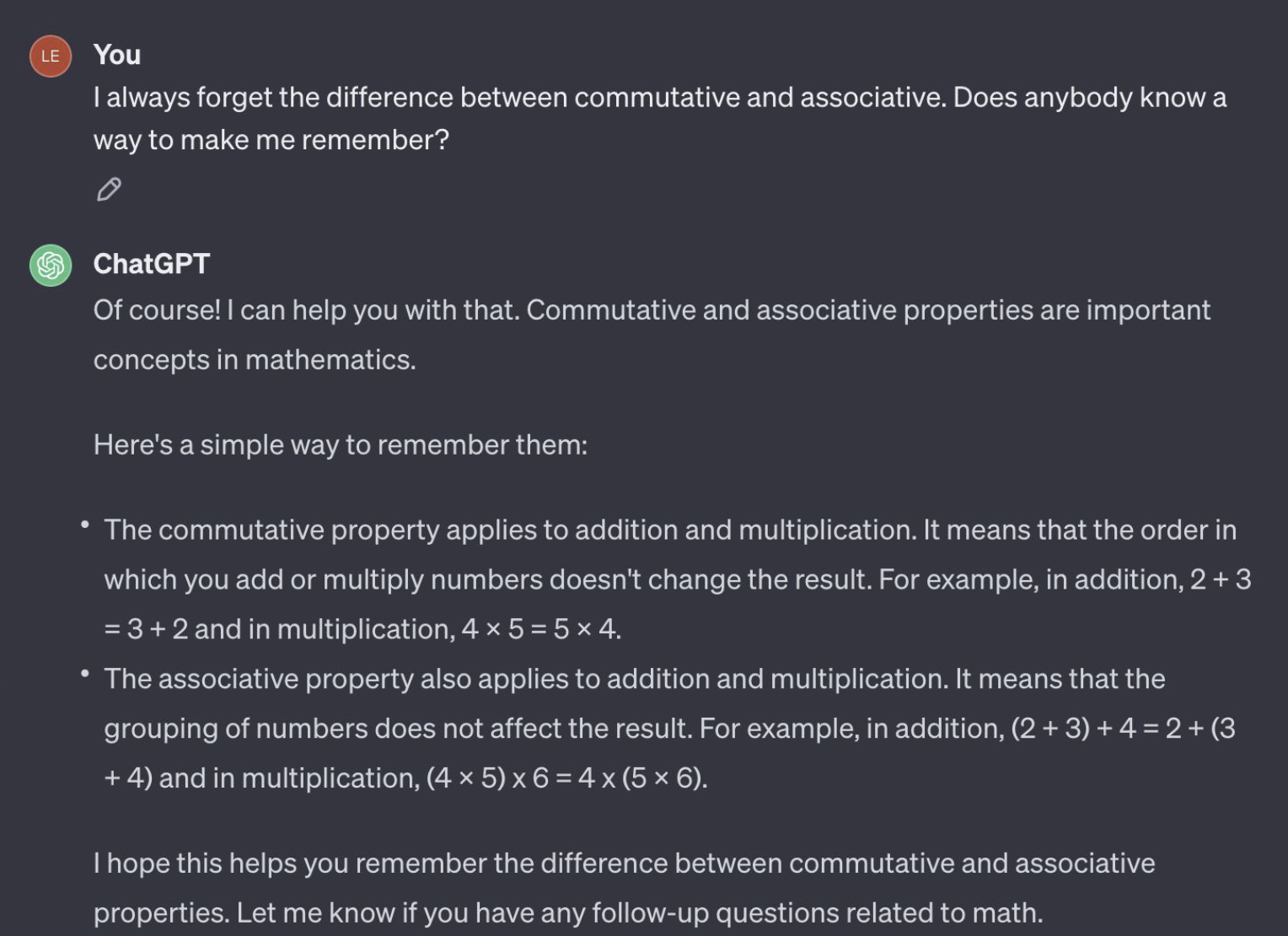

- I always forget the difference between commutative and associative. Does anybody know a way to make me remember?

We’ll be sticking with that last question as our illustrative example. We identified 51 conceptual questions from the Math Nation forums will be our test set for our first version of the Rori conceptual Q&A feature. Each question represents a tutoring opportunity detached from a specific “problem set”. I like these questions because they have high external validity: they’re relatively diverse, and students really did ask them.

Answering conceptual student questions with ChatGPT

How does ChatGPT (3.5) do answering these questions? Pretty good! Here’s the response to the commutative vs associative question:

ChatGPT tells us that “commutative” is when the order in which you add or multiply numbers doesn’t change the result, and “associative” means grouping of numbers, which I would say is correct.

But is that a good answer to the question? Correctness is not enough! One of the core challenges with using generated text in student-facing interfaces is that it can be correct or even “helpful” while being totally irrelevant to what the teacher is doing in the class. We want the language and concepts used in generated texts to reflect a student’s grade level, and more generally for there to be alignment between the technology and the curriculum. We might also be concerned about cultural relevance, particularly in the case of Rori, because we know that LLMs like ChatGPT show significant western cultural biases because of the distribution of the data they’re trained on, which might make responses less relevant to West African students.

How can we build student Q&A systems that fulfill these diverse (and quite vague) criteria? I think it’s useful here to think about what qualities the responses need to have for us to trust them. Here’s one way that I like to think about the design space for these systems. Let’s imagine a continuum between a conventional information retrieval system and the use of a minimally constrained generative text model like an LLM.

Continuum between conventional IR and LLMs for student Q&A

Continuum between conventional IR and LLMs for student Q&A

We’ll assume we have a query of some kind from the student: a conceptual question, or just some kind of information need. In the conventional information retrieval model, this is just a pure information extraction task: identify the text excerpt from some corpus that is most relevant to a student’s question. This has a lot of benefits! The text shown to the user is by-definition trusted: it has been vetted or even written by the educator, and it exists in a familiar context, so it is likely both correct and meets those other criteria, like being grade appropriate.

But there are downsides to information extraction systems: they’re inflexible, it’s hard to personalize the response, and you’re depending on your retrieval corpus to not only contain an appropriate response to the student’s question, but also that your retrieval system is powerful enough to find that appropriate response. It’s in that context that instruction-fine tuned large language models like ChatGPT start looking really amazing: they echo the language used by the student, and generally respond directly to the content of the question. Unfortunately, the LLM response might be totally inappropriate for the student. For example, it might be factually incorrect while sounding authoritative: not a good combination. Ideally, we’d like to tune between these two extremes, and there is a long history of hybrid models that try to do so. But because we’re so enamored with large language models, and their fluency is so much better then the previous generation of models, we might want to lean as close to the ChatGPT side of things as we can.

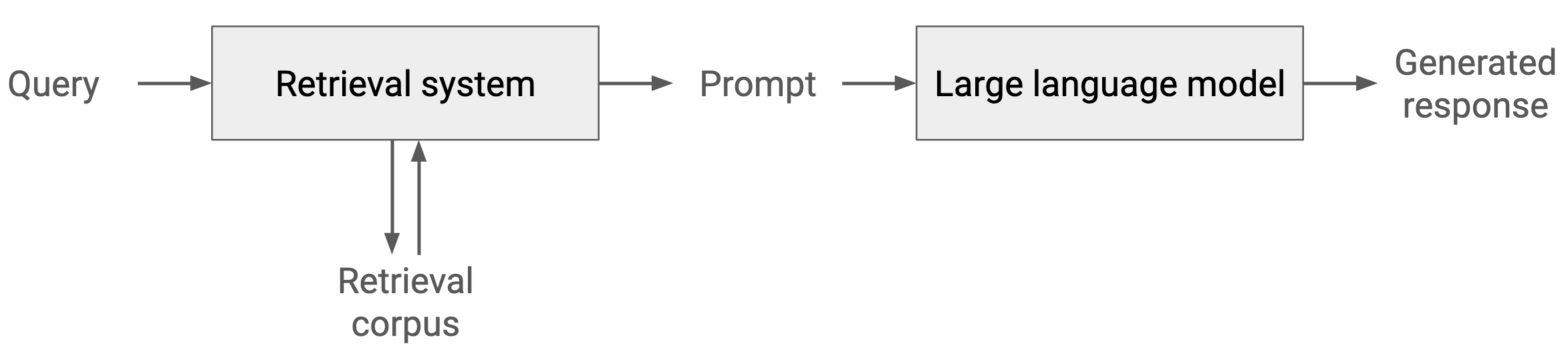

While there are many approaches we might use, the most prominent approach is to use retrieval-augmented generation (RAG). By retrieval-augmented generation, I mean a combination of prompt engineering and a retrieval system. Without RAG, we provide a textual prompt to condition the model’s generated response. In the basic use case, we’d do prompt engineering. We could incorporate the student’s question in the prompt in some way until the generated responses start looking good. Retrieval-augmented generation extends this basic approach by incorporating a retrieval system in the mix. Now, we take the student’s query and pass it to a retrieval system, identifying zero or more texts from a corpus and incorporating those retrieved texts into the prompt before we pass it to the large language model.

Tangibly, to do retrieval-augmented generation for conceptual Q&A, we need to add a retrieval system to our architecture. And to do that, we need to make a lot of small decisions. Because the technique is so general—you can use it for any text generation task—learnings from one task context might not generalize to middle-school math conceptual Q&A. The theory of why RAG works to improve the quality of the generated responses is, unfortunately, somewhat unclear. It’s basically the theory of why in-context learning works. That includes techniques like few-shot prompting, “think step by step”, and other prompt engineering stuff, as well as more complex approaches like tree of thought. The evidence is currently pretty unclear here, but including texts in the prompt is basically a very stupid way of approximating the posterior predictive distribution: it gets us into the right probability space. Intuitively, that means RAG will be useful for providing formatting and language that we want our answer to contain.

It matters what texts we have in our retrieval corpus and how we format those texts when we include them in the prompt. It also matters what our prompt is to begin with, what retrieval system we’re using, and what large language model we’re using. We can think of all of these decisions as hyperparameters, so we might imagine some kind of automated evaluation system that would let us try a bunch of different hyperparameter combinations and end up with something reasonable. I’m going to spend the rest of this post complaining about the challenges of evaluation and why we can’t do that yet, but for now I want to make it clear how we implemented our system and walk through some of these many decisions.

Implementing a retrieval-augmented generation system

Let’s start with the large language model and the prompt. We used GPT-3.5, for cost reasons and speed of development—an underrated factor! To generate responses appropriate for the Rori context, this is the base system prompt we used, and it seemed to work pretty well, although it can certainly be improved. Here’s the prompt we used to generate the earlier response, for that question about commutative vs associative properties:

You are going to act as a mathematics tutor for a 13 year old student who is in grade 8 or 9 and lives in Ghana.

You will be encouraging and factual.

Prefer simple, short responses.

If the student says something inappropriate or off topic you will say you can only focus on mathematics and ask them if they have any math-related follow-up questions.

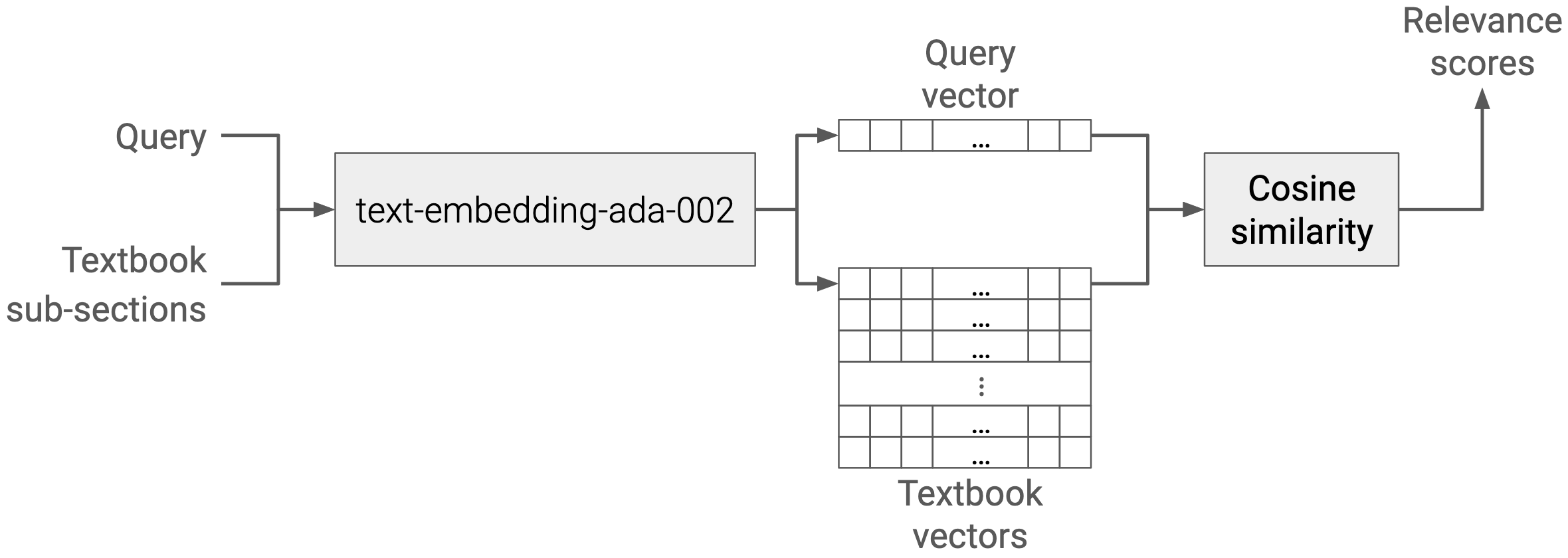

The more interesting decisions are about the retrieval system: what text corpus should we use to have a shot at improving our responses? We decided to use a math textbook, since it’s been vetted by the fires of real classroom use. In this case, we use the Prealgebra textbook released by OpenStax, because it’s a trusted, high-quality resource and is freely available under a permissive license (CC-BY)! One benefit of using a textbook is that it’s structured: it comes with semantically-related chapters, sections, and sub-sections, and we can use that structure when we retrieve texts. To actually do retrieval with this textbook data, we need to index it in some way so we can identify the most relevant sections based on a student’s query. To do that, we again relied on OpenAI’s APIs: their ADA embeddings are a way to get a dense vector representation of both the student’s query and the individual sub-sections of the textbook.

To rank the most “relevant” sections, we can compute cosine similarity between the vectors for the query and the textbook sub-sections. The prealgebra textbook has 247 sub-sections, and we produce a score for the similarity of each sub-section to the query relatively quickl (<200ms on average). Once we have the relevant scores, we get to exploit the textbook’s semantic structure by using “parent retrieval”: rather than just providing the single sub-section that’s most relevant to the query, we include the whole section, so that the full context for that sub-section is available at inference time.

By cosine similarity, the most relevant sub-section to the commutative vs associative query is a subsection with the heading “simplify expressions using the commutative and associative properties”. Rather than including just that one sub-section as context, we include all the sub-sections from that section: “Commutative and associative properties”. We insert that whole section into the prompt.

How can we tell if using RAG improved the quality of the generated response? On our Q&A continuum, have we actually moved toward a more trusted, vetted, student-appropriate response by using RAG? The concept we’re talking about here has been described by a long history of information retrieval research: they call this concept groundedness. Groundedness as a construct won’t capture all the dimensions mentioned earlier, but it will help us understand if we’re moving in the direction of responses that are grounded in our vetted, trusted textbook.

Measuring groundedness

How can we determine if our responses are more or less grounded? As a starting point, there are many automated groundedness metrics. Let’s consider Knowledge F1 (K-F1), a simple groundedness metric. K-F1 is a bag-of-words based metric: we tokenize the response generated by the LLM and the retrieved textbook section and compute the overlap between these two token sets. We compute precision and recall with the retrieved text’s tokens as the ground truth and the generated response’s tokens as the prediction, and finally compute K-F1 by taking the harmonic mean of precision and recall.

Sidebar: K-F1 vs K-F1++

K-F1 is quite a strict metric; you get no credit for synonyms, and you get punished for using superfluous words.

For LLM evaluation, K-F1 can be particularly punishing because of the tendency of instruction-fine-tuned LLMs to repeat words from the question.

To avoid punishing that type of repetition, Sabrina Chiesurin and some folks at Alana AI proposed K-F1++, a variant metric that removes the words in the query from both token sets. In our experience, K-F1++ is a much better groundedness metric for LLM responses.

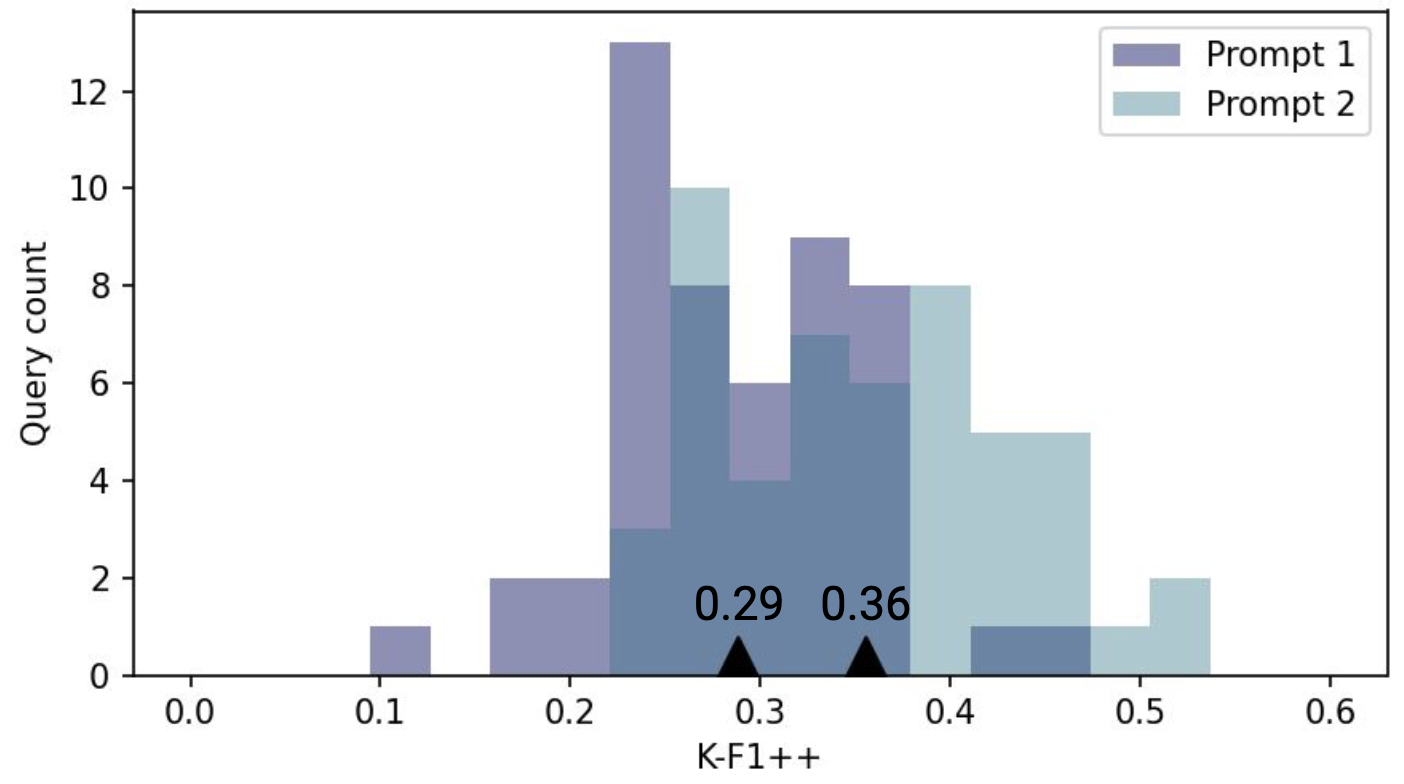

Using K-F1++, we can now evaluate the responses over all 51 of our student queries from Math Nation. That will enable us to compare the groundedness of two (or more) different prompts. To create effective prompts, we can use prompt engineering: GPT-3.5 is tuned to follow instructions, so we can just include instructions in the prompt for the response to be more grounded. Here’s what we add to the prompt, right after “You will be encouraging and factual”:

Use examples and language from the section below to format your response:

===

Use the Commutative and Associative Properties: Think about adding two numbers, such as 5 and 3… {rest of the textbook section}

===

If we visualize the distribution of K-F1++ scores, we can compare prompts. Here, two different prompts have a mean K-F1++ score of 0.29 and 0.36. With this evaluation process, we can manually adjust the prompt to achieve the desired level of groundedness.

Prompt engineering + RAG to improve groundedness

Let’s compare the level of groundedness for a few different prompts. In this study, we considered three conditions:

- None: no use of RAG at all.

- Low Guidance (Prompt 1): Use RAG, with the additional prompt guidance “Use examples and language from the section below to format your response:”.

- High Guidance (Prompt 2): Use RAG, with the additional prompt guidance “Reference content from this textbook section in your response:”.

For K-F1++, we can see that the High guidance condition is indeed more grounded than the Low guidance condition. This pattern holds for two commonly-used model-based groundedness metrics as well: BERTScore and BLEURT.

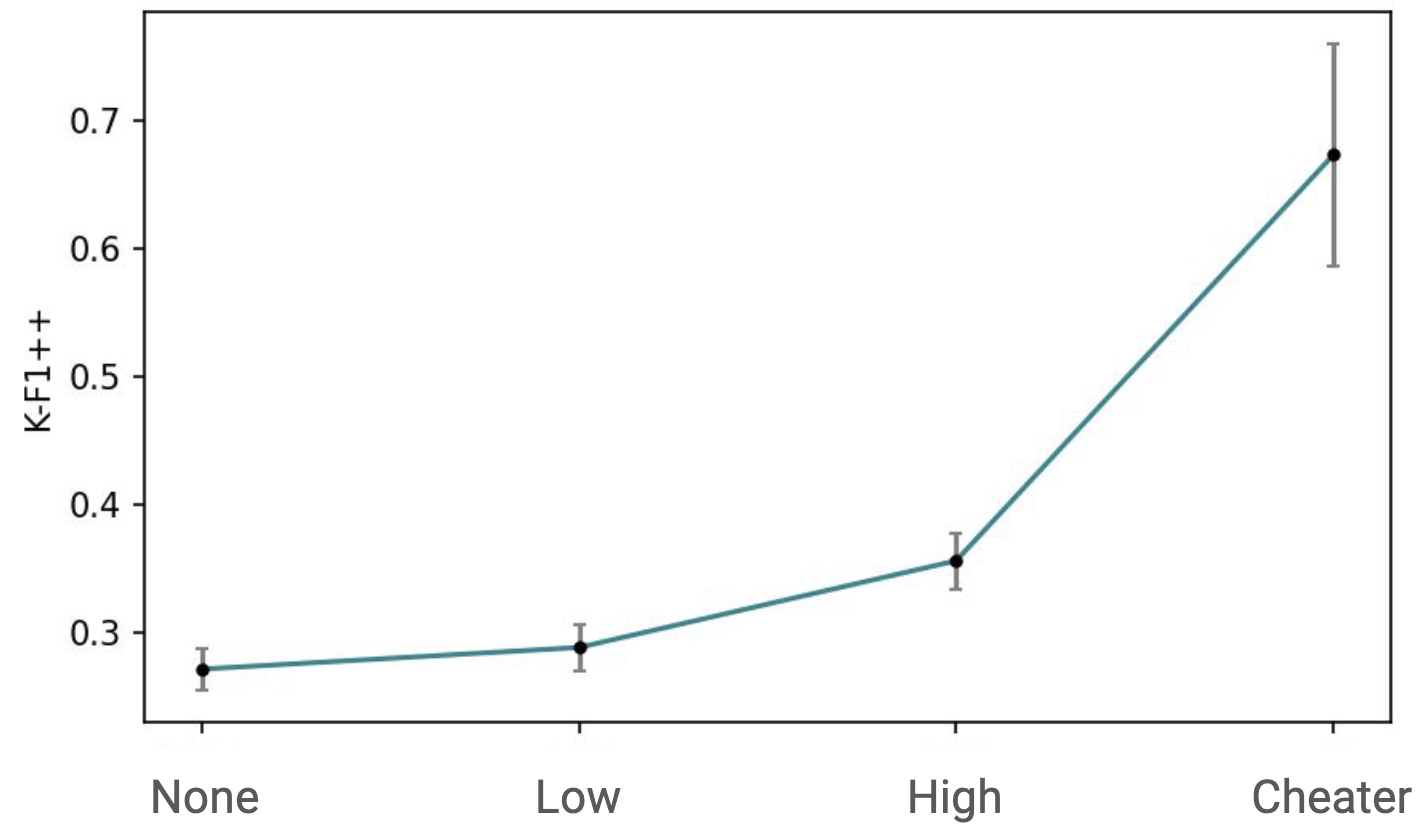

These results look expected, but I have trust issues with automated metrics. For groundedness, it seems like we might be able to increase the value of the metric but without a corresponding increase in the things we hope groundedness correlates with, like correctness. So I added a “Cheater” prompt that doubles our K-F1++ score.

These responses are garbage! I call this the “cheater” condition because it just updates the prompt to say: “Given a middle-school math student’s question, you will identify the most relevant section from the textbook.” This should make us concerned. Not only do we need some other way to tell if we’re increasing groundedness in a “good” way, but also we might worry that there’s a trade-off with other things we might care more about, like the relevance of the response and its correctness.

That paper from Alana AI gives us a very useful perspective on groundedness by distinguishing it from a related construct that they call faithfulness. They say that they “consider a response to be grounded when it (or a paraphrase of it) is found in the retrieved document. They consider a response to be faithful if, in addition to being grounded, it answers the question and follows from the dialogue. But we don’t have good automated metrics for faithfulness! In fact, we don’t even have good evaluation processes for faithfulness. This is a great opportunity for future work and for interdisciplinary collaboration between the measurement people and the design people: give us surveys, rubrics, and taxonomies appropriate for assessing faithfulness!

In the meantime, we can try to better understand how RAG affects response quality by asking people. We’ll have student data Soon™, but for this work we just asked 9 educators to fill out a survey.

Surveying educators about response quality

The main thing we care about is how RAG affects the quality of responses. For that, we preferred comparative preference rankings: presenting people with different LLM responses to the same student question and asking our annotators to rank them. We also want to know how much we can trust our automated groundedness metric, so we used an existing groundedness scale, essentially as a manipulation check.

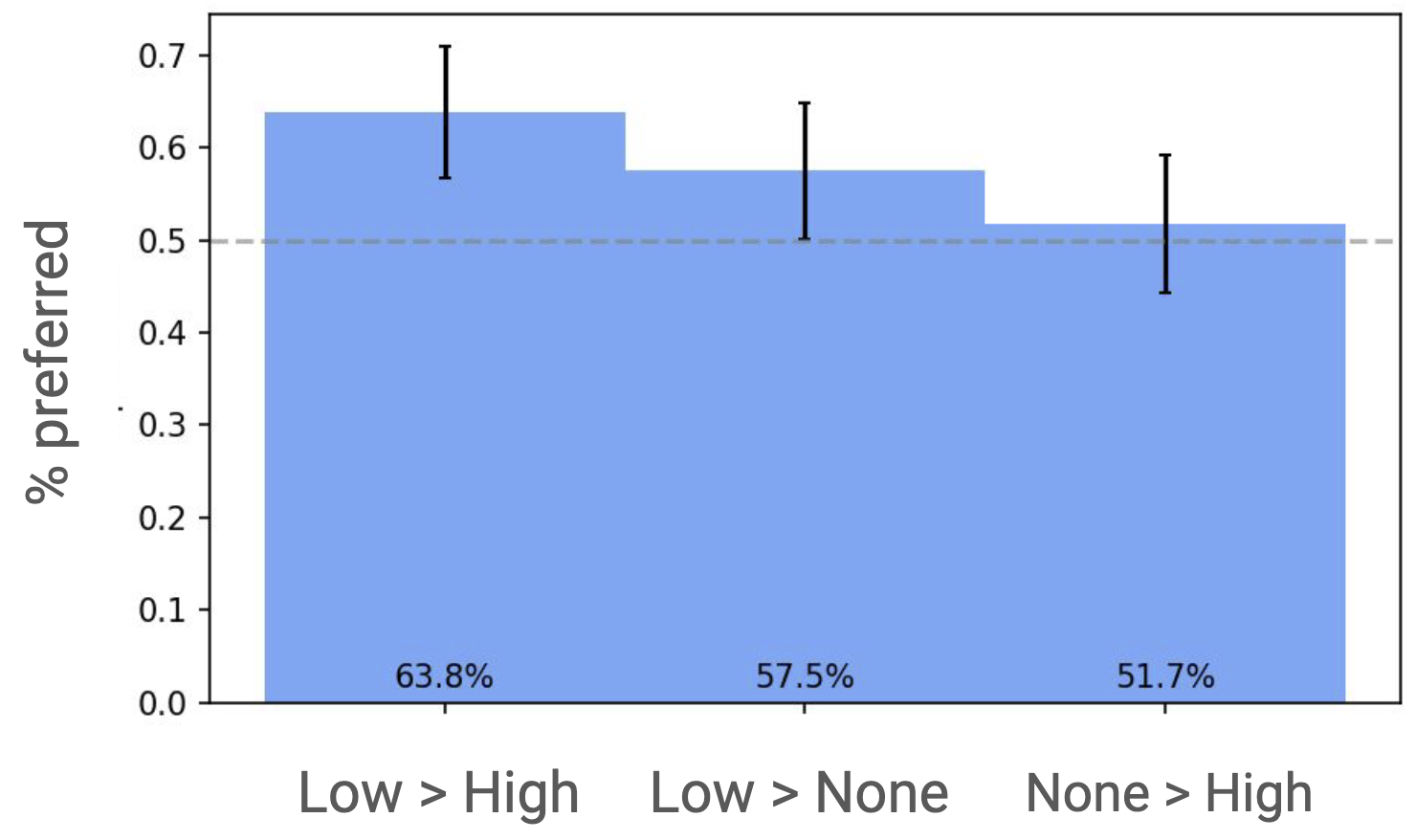

Pair-wise respondent preferences for all rankings. RAG can help, but too much guidance can hurt!

Pair-wise respondent preferences for all rankings. RAG can help, but too much guidance can hurt!

Our primary result:

- RAG can help. Respondents preferred RAG-generated responses in the low-guidance condition over responses generated without RAG 57% of the time.

- [Too much] RAG can hurt. Respondents preferred low-guidance responses over high-guidance responses 64% of the time.

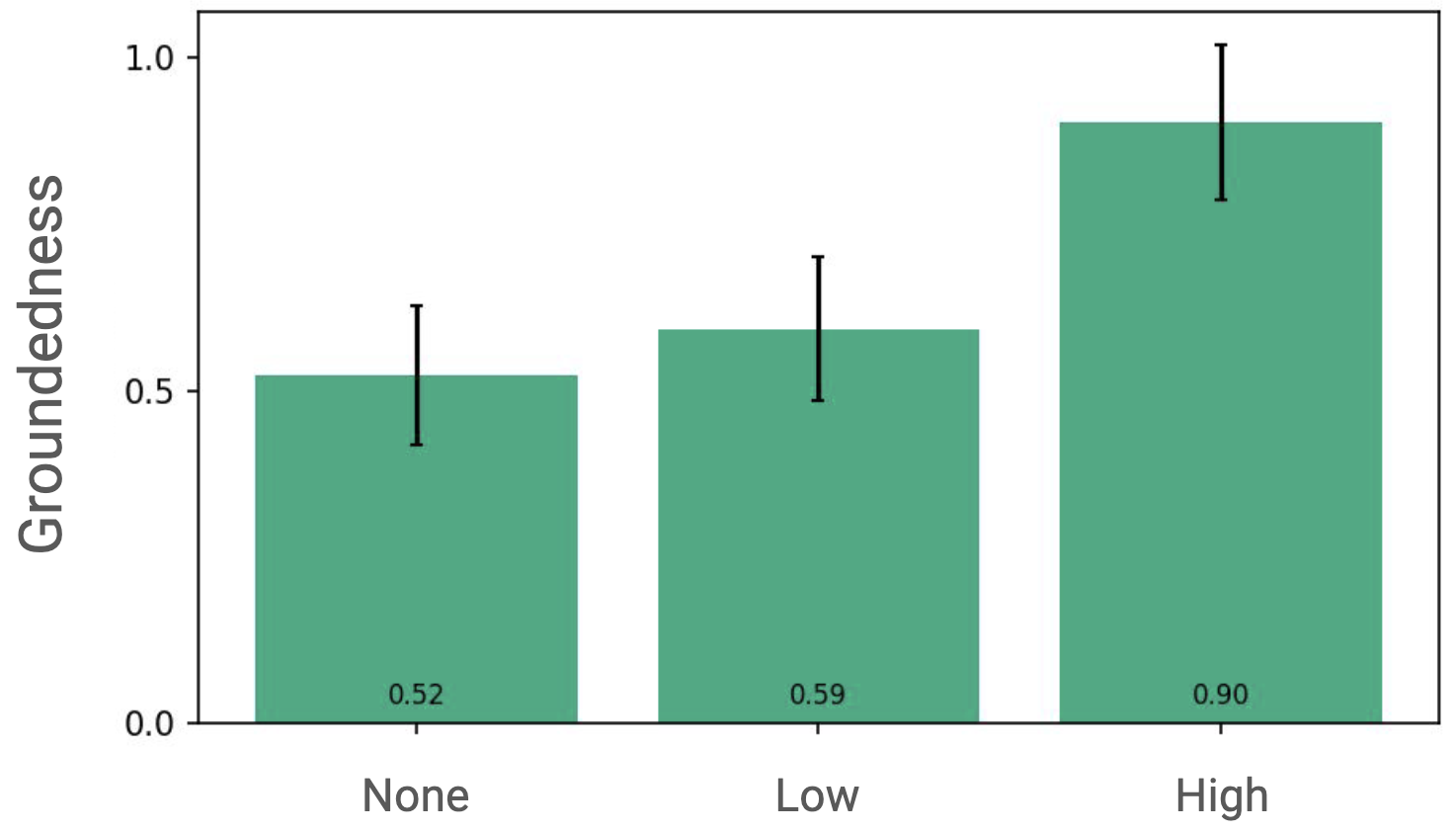

Groundedness ratings

Groundedness ratings

Does using RAG actually increase groundedness? No indication that it does in the low-groundedness condition. (95% confidence intervals shown, p > 0.05.) But respondents definitely could tell that the high-guidance responses were more grounded.

Thinking just about the low-guidance condition, we see that RAG responses are preferred slightly compared to responses generated without RAG, and perceived groundedness will be the same (or a bit higher). I call that a win! RAG can probably help, and it probably won’t hurt. That’s important, because we might want to use RAG even if it did hurt response quality.

If we care more about groundedness than about human preference, then we can use prompt engineering to make that trade-off. By the way, we can compare the human annotations to our automated groundedness metrics: the correlation is 0.52 between perceived groundedness and K-F1++, which seems pretty good to me. That should increase our trust a bit in using the automated metrics - although risks still exist, as the Cheater condition shows.

Sidebar: does relevance affect respondents’ preferences?

How relevant is the retrieved textbook section to the student’s question?

Intuitively, we might think that the reason high guidance responses are ranked lower by survey respondents is because the retrieved text is low relevance. (After all, large language models can be easily distracted by irrelevant context.)

We annotated for document relevance (using an existing 4-point scale), and we do see the expected relationship with groundedness: responses with more relevant textbook sections in the prompt are also perceived to be more grounded (r=0.56).

But, we found no correlation between relevance and preference!

That’s a puzzle to uncover in future work, although we do more speculation in the paper.

We’re currently continuing our exploration of retrieval-augmented generation by testing these Q&A processes with students. We’re excited to start getting actual preference data from students as well as to see whether our preference results hold beyond the first conversational turn of a Q&A session.

I’ll point at the end here to two compelling research directions that others might have thoughts about or what want to pick up here.

- Design: how do we best incorporate these kind of Q&A features in Rori?

- Evaluation: how can we create repeatable processes or automated metrics for capturing groundedness, correctness, and trustworthiness?

I’ll end by pointing to a nice paper laying out major open opportunities for research in NLP right now, emphasizing the importance of evaluation. The problem of long text evaluation is very much not solved. If we had good processes for evaluation, we could iterate a lot more quickly and make more principled decisions while building RAG systems.

Thanks for reading! Take a look at the paper for more detail. Find the code and data here. Glance at the poster summary (PDF) or my 1-minute summary on YouTube.

Cite this work:

Zachary Levonian, Chenglu Li, Wangda Zhu, Anoushka Gade, Owen Henkel, Millie-Ellen Postle, and Wanli Xing. 2023. Retrieval-augmented Generation to Improve Math Question-Answering: Trade-offs Between Groundedness and Human Preference. In NeurIPS’23 Workshop on Generative AI for Education (GAIED), New Orleans, USA. DOI:https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2310.03184