Research paper: Ideological differences in the expanse of the moral circle

In 2019, Waytz et al. published “Ideological differences in the expanse of the moral circle” in Nature Communciations.

This paper uses the concept of moral circles: “the circle of people or other entities in which you are concerned about right and wrong done toward them”. For example, many people are concerned about right and wrong done toward their immediate family, but less concerned about right and wrong done toward rocks or trees.

The paper presents a variety of studies, but I was most interested by a particular survey study investigating how people allocate their moral concerns within moral circles.

In this study (study 3a), they asked 131 US residents to complete two tasks:

- Zero-sum allocation of “moral units” across 16 increasingly large categories.

- Indicating the extent of their moral circle.

They were trying to test the hypothesis “that liberals relative to conservatives will show more moral concern toward nonhuman (relative to human) targets”.

Here’s what participants were told for the first task:

In this section, we would like to think about your capacity to help, to give, to be charitable, to show empathy, and to be generous—in other words, your capacity to behave morally. We can think about people having different amounts of moral units—like currency—that they can spend on others and can allocate to different moral circles. Some people devote all of their moral units to one circle whereas others try to divide up their moral units amongst multiple circles. Again, by moral circle, we mean the circle of people or other entities in which you are concerned about right and wrong done toward them.

Here’s what participants were told for the second task:

On this page, we would like you to indicate the extent of your moral circle. By moral circle, we mean the circle of people or other entities for which you are concerned about right and wrong done toward them. This depiction demonstrates that people have different types of moral circles. At the innermost circle, some people care about their immediately family only, and at the outermost circle, people care about the entire universe - all things in existence. Please use the following scale and select a location that depicts the extent of your moral circle.

- all of your immediate family

- all of your extended family

- all of your closest friends

- all of your friends (including distant ones)

- all of your acquaintances

- all people you have ever met

- all people in your country

- all people on your continent

- all people on all continents

- all mammals

- all amphibians, reptiles, mammals, fish, and birds

- all animals on earth including paramecia and amoebae

- all animals in the universe, including alien lifeforms

- all living things in the universe including plants and trees

- all natural things in the universe including inert entities such as rocks

- all things in existence

Please click on a number that depicts the extent of your moral circle. Note that in this scale, the number you select includes the numbers below it as well. So, if you select 10 (all mammals), you are also including numbers 1-9 (up to ‘all people on all continents’) in your moral circle.

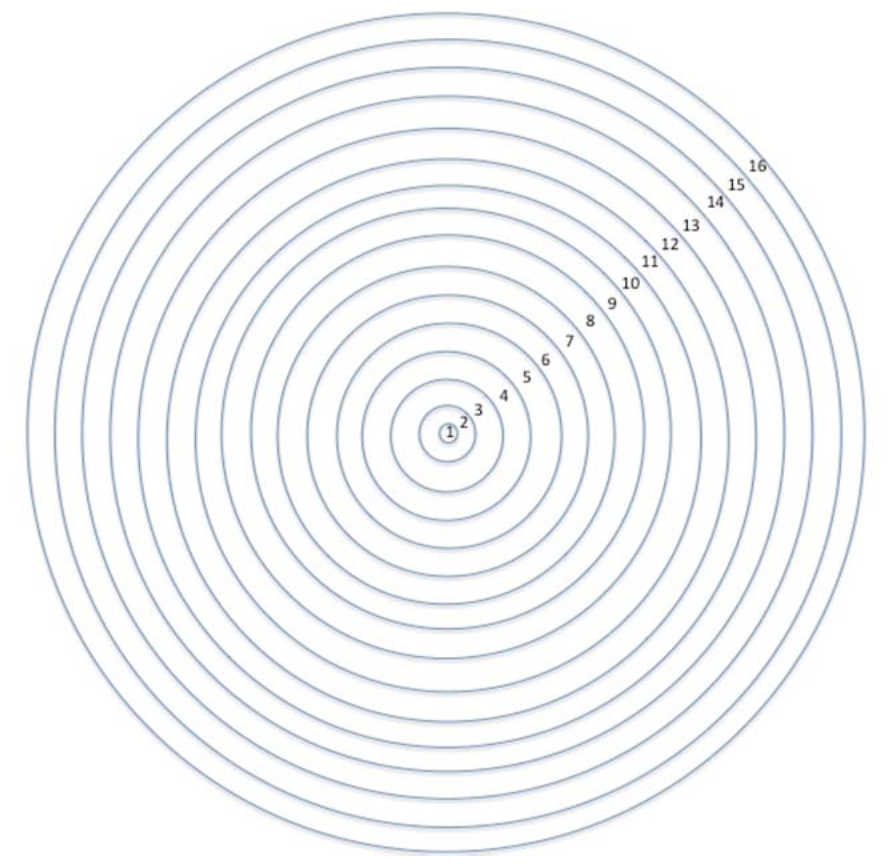

The moral circle diagram shown to participants for tasks 1 and 2.

The moral circle diagram shown to participants for tasks 1 and 2.

Who were the participants?

One hundred thirty-one United States residents (53 male, Mean Age = 35.82, SD = 13.76) were recruited from the Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) marketplace for a small monetary reward. …. Participants completed the study using Qualtrics software, including an ideology measure that contained seven options (very liberal, liberal, slightly liberal, moderate, slightly conservative, conservative, very conservative). …. Our sample included 64 liberals, 31 moderates, and 36 conservatives.

Here’s the detailed ideology breakdown:

| Political ideology | Participant count |

|---|---|

| Very liberal (1) | 11 |

| Liberal (2) | 35 |

| Slightly liberal (3) | 18 |

| Moderate (4) | 31 |

| Slightly conservative (5) | 10 |

| Conservative (6) | 16 |

| Very conservative (7) | 10 |

Let’s dive into their results, using the provided panel data to reproduce the figures.

Task 1: Allocation of moral units

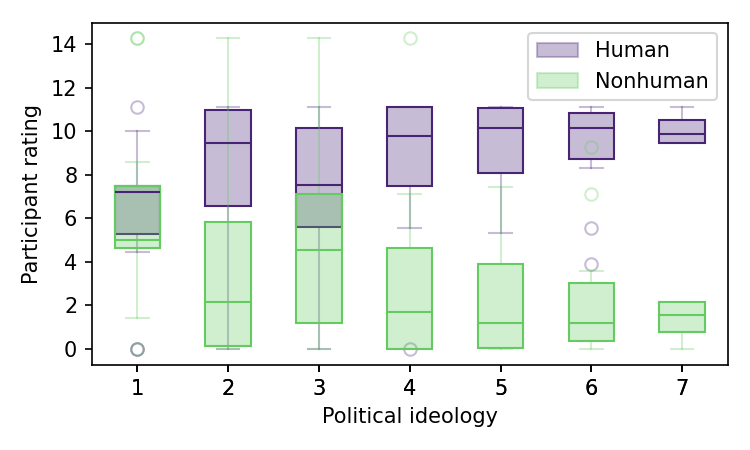

First, they find that more conservative people allocate more points to humans compared to non-humans. They don’t describe how they compute the “rating” shown in their figure, but it presumably reflects the zero-sum allocation assigned to the human entities (rings 1-9) vs the nonhuman entities (rings 10-16).

Recreation of Waytz et al.’s Figure 4 as a boxplot.

Recreation of Waytz et al.’s Figure 4 as a boxplot.

As a refresher on box plots: the boxes range from the first quartile to the third quartile and the median is indicated by a line within the box. Per the Matplotlib defaults, the whiskers extend from the box to the farthest data point lying within 1.5x the inter-quartile range from the box.

The general trend here seems fairly weak to me. One possibility is that people who identify as very liberal differ systematically from others; perhaps “people who extend moral concern to nonhumans” is a group that is also likely to self-identify as very liberal. But only 11 participants identified as very liberal, so even the existence of a difference within liberal-identifying people is pure speculation on my part.

Task 2: Extent of moral circle

The extent task finds that conservatives generally clicked closer to the center then liberals.

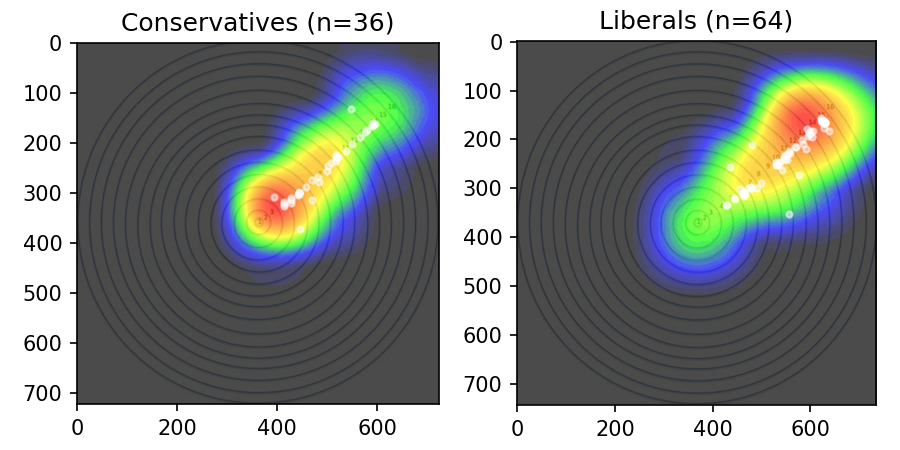

Recreating the figure from the paper was tough, because the provided data is x/y coordinates within an image, but without the exact image I’m not sure I’ve positioned the clicks correctly. After manual adjustment, here are the clicks (in white) superimposed over a screenshot of Figure 5 from the original paper.

Superimposing the individual clicks over Waytz et al.’s Figure 5.

Superimposing the individual clicks over Waytz et al.’s Figure 5.

I don’t know what density estimation method they used to make this heatmap, but there does seem to be a real difference here. Adam Waytz told me via email that the original heatmaps are generated by Qualtrics, who don’t describe their density estimation approach. Here’s my recreation of Figure 5 using Gaussian kernel density estimation and a manually-selected bandwidth.

Recreation of the Figure 5 heatmap using SciPy to estimate a Gaussian density from participants’ clicks.

Recreation of the Figure 5 heatmap using SciPy to estimate a Gaussian density from participants’ clicks.

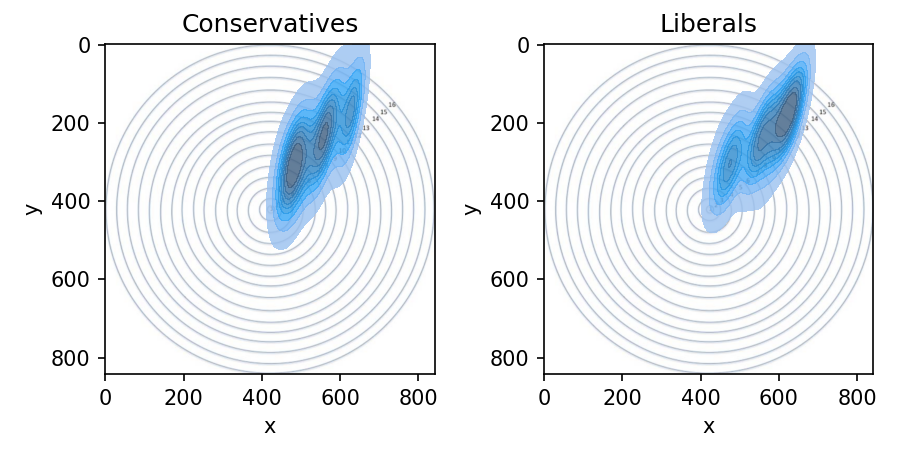

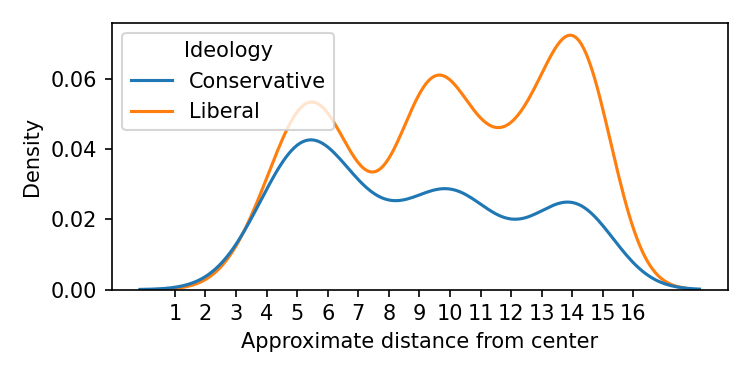

If we assume that all circles are an equal width (which is clearly not true from eye-balling the figure), we can compute the distance from the center, again estimating density using a Gaussian kernel.

Recreation of the Figure 5 heatmap using SciPy to estimate a Gaussian density from participants’ clicks.

Recreation of the Figure 5 heatmap using SciPy to estimate a Gaussian density from participants’ clicks.

This estimate is necessarily approximate; I don’t know if I’ve correctly mapped the distances, so the specific extent categories are likely inaccurate. But we can see a clear trend that liberals were more likely to click somewhere in the ballpark of “all animals/aliens/living things”.

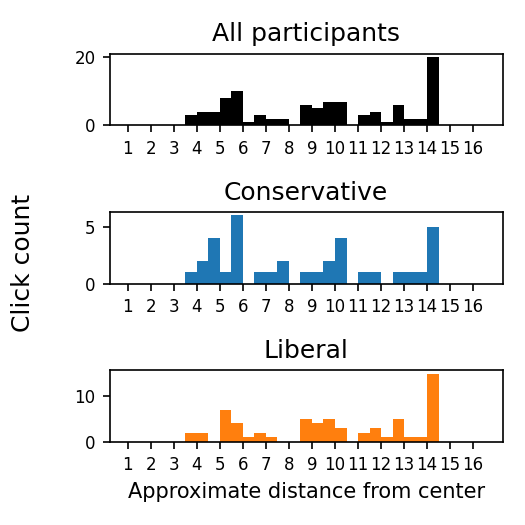

Histograms of participant clicks. Don’t trust the categorization of clicks into entity categories.

Histograms of participant clicks. Don’t trust the categorization of clicks into entity categories.

In general, I think this “moral extent” task is an interesting one. I’ve love to see a more qualitative study exploring how people reason about their moral extent. Detailed data from Task 1 could be useful for this question; do people assign zero moral concern to those entities outside the extent of their moral circle, or just relatively much less?

The authors argue that these ideological differences in moral concern allocation and extent of moral circle reflect a difference between universalism and parochialism. This framing is interesting, and I’d like to see more rigorous exploration of these concepts as philosophies that may or may not align with Americans’ political ideologies.

If you want to play with the data yourself, you can check out the Jupyter Notebook that creates the plots in this post on GitHub.

Further Reading

- Benjamin Enke. “Moral Boundaries”. September 2023. NBER Working Paper.

- Sigal Samuel. “Should animals, plants, and robots have the same rights as you?”. April 2019. Vox.

I’ve previously written about political communication on social media.